Roughly 7,540 Excess Deaths Caused by Panic Buying & Hoarding in the UK

Increased virus transmission during 5 weeks of 2020 resulted in approximately 2,621 excess flu and pneumonia deaths and (when modelled to COVID-19) approximately 4,919 excess COVID-19 deaths. This coincides societal fear, including panic buying and stockpiling of hygiene goods.

In my last post, I summarised some of the existing evidence on the risk/reward of COVID-19 lockdowns (and mask wearing). In lieu of gold-standard Randomised Control Trial evidence, we are increasingly reliant on observational data. In this post, I wish to dive into some of the emerging data on the efficacy of lockdown.

The Impact of Lockdown on Flu

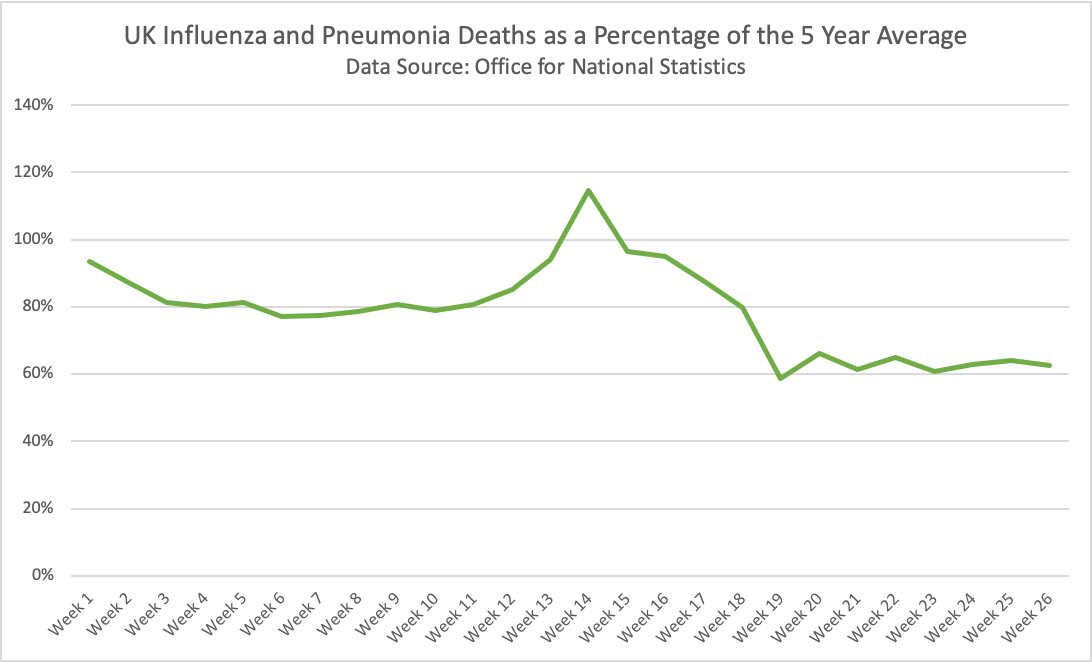

Whilst we lack Randomised Control Trial evidence on lockdown measures, we do have observational data. Given SARS nCoV-19 is by definition novel; we only have death data starting from Week 11 of 2020 for COVID-19 specifically. We do, however, have 5-year average data for other respiratory infections (such as influenza), and this can help us understand the impact of lockdown.

Given flu has a relatively short incubation time (about 2 days until symptoms), we can seek to infer how various different interventions have fared.

On Week 10 of 2020 (2nd to 8th March), the number of influenza and pneumonia deaths began to grow exponentially. This peaked on Week 14 (30th March to 5th April), returning to normal levels on Week 18 (27th April to 3rd April). During this time, we saw people stockpiling food and empty shelves in supermarkets.

On the 23rd March (at the very start of Week 13), Prime Minister Boris Johnson placed the United Kingdom in lockdown. Flu deaths increased through the following week before starting to decline the week after.

In summary:

| Weeks | % flu and pneumonia deaths as 5 year average |

|---|---|

| 1 - 10 | 82% |

| 11 - 18 | 92% |

| 19 - 26 | 63% |

Panic Deaths

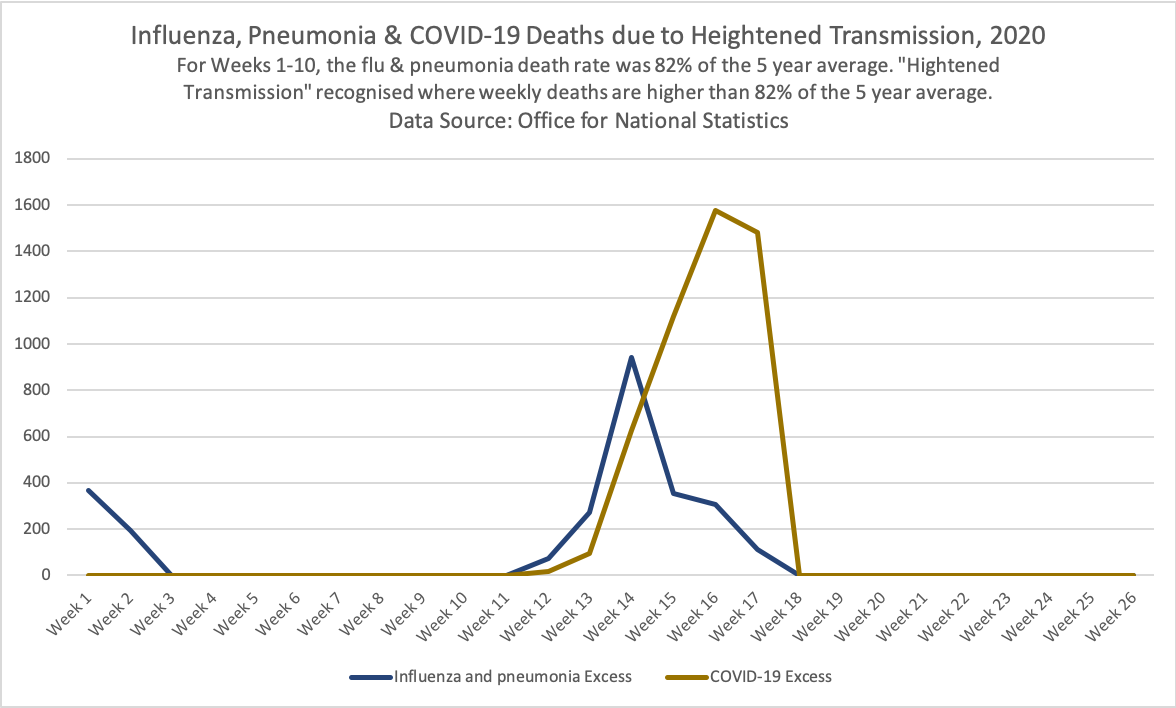

For Weeks 1-10, the average flu & pneumonia death rate was 82% of the 5 year average. We define "Heightened Transmission" where weekly deaths are higher than 82% of the 5 year average (and we count those in excess of the 82% baseline metric). You can see this plotted below for the entirety for 2020:

Increased virus transmission between solely Weeks 12 to 17 resulted in circa 2,621 excess flu and pneumonia deaths. Uniformly modelled to COVID-19, there were circa 4,919 excess COVID-19 deaths.

This indicates there were 7,540 excess deaths caused by influenza, pneumonia and COVID-19 over these 5 weeks (from the 16th March to the 26th April). This correlates with activities such as panic buying in supermarkets and hoarding causing supermarkets to encounter shortages of toiletries.

Impact of Lockdown

From Week 19 onwards, flu and pneumonia deaths are 63% of their 5 year average; this is a ~23% decrease when measured against the first 10 weeks of 2020. That said, given the heightened transmission of flu and pneumonia (alongside COVID-19 deaths) between Weeks 11 and 18; we may now be seeing a reduction in deaths due to mortality displacement. Displaced mortality means that after a period of heightened deaths, deaths fall below average levels as there are less vulnerable members of the population.

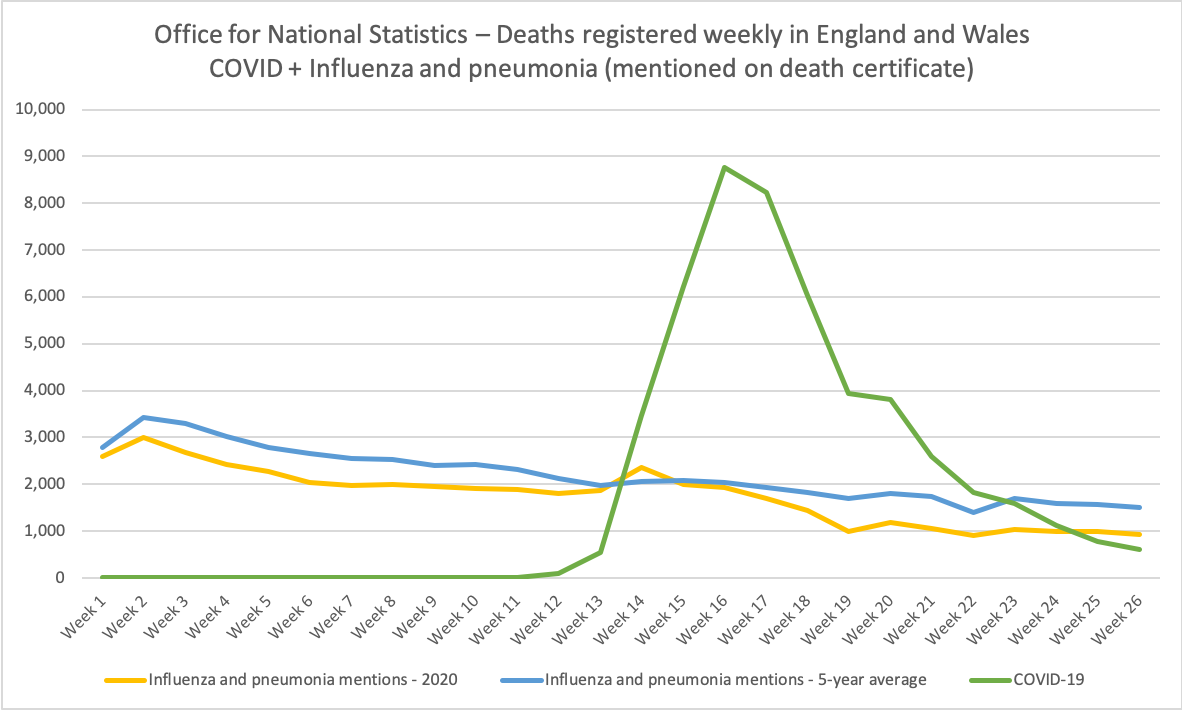

Whilst flu and pneumonia deaths have decreased, they now appear to circulate at a consistent rate. Despite claims that COVID-19 is more virulent than flu, COVID-19 deaths have declined far more quickly.

This phenomenon also does not seem to be explained by COVID-19 specific measures, recall universal testing only became available in the UK on the 27th May (during Week 22, as the peak had already been passed by 6 weeks). This highlights our limited virological understanding of COVID-19 (including that of T Cell immunity).

Limitations

There are, of course, some limitations to such an approach; the data here is sourced from the UK's Office of National Statistics and I've previously highlighted the flaws in statistical evidence they have produced. With this data, it is important to remember it is the cause-of-death determined by a doctor on the balance of probabilities; not necessarily with a positive test. That said, it provides us real-world measures on the impact of lockdown measures that we have so far lacked.

It is important to note that there is evidence that co-infection of flu and COVID-19 can increase mortality and there is likewise evidence that other respiratory infections have been confused for COVID-19 as the cause-of-death on some death certificates. The University of Oxford's Centre for Evidence Based Medicine has noted that the number of deaths attributed by the ONS to COVID-19 is substantially higher than those attributed to a death with a positive test by Public Health England.

Given the similarity of symptoms between COVID-19 and flu and the limited UK test capacity at the start of the pandemic; some of those with symptoms of flu will have self-isolated, going beyond the core of the lockdown policy.

By using five-year averages when calculating changes in virus circulation, we can account for seasonal adjustments in the virus - though the differences in seasonality between COVID-19 and other coronaviruses is not yet fully understood.

Conclusion

In this post, we've demonstrated that observational data shows that during Weeks 11 to 19 of 2020 death data indicates there was an increase in virus circulation in the UK, coinciding with an environment of general panic within society resulting in panic buying and hoarding of hygiene toiletries.

The Director-General of the Norwegian Institute for Public Health, Camilla Stoltenberg, recently remarked in an interview that COVID-19: "shows how your society works in a very open way" and that it "truly exposes how good social cohesion is, how trust is, what the divisions in society are".

There is perhaps no country where this is more true than Britain. In March, we saw a video of an NHS critical care nurse left in tears after finding no fruit or vegetables in her supermarket after a 48-hour shift.

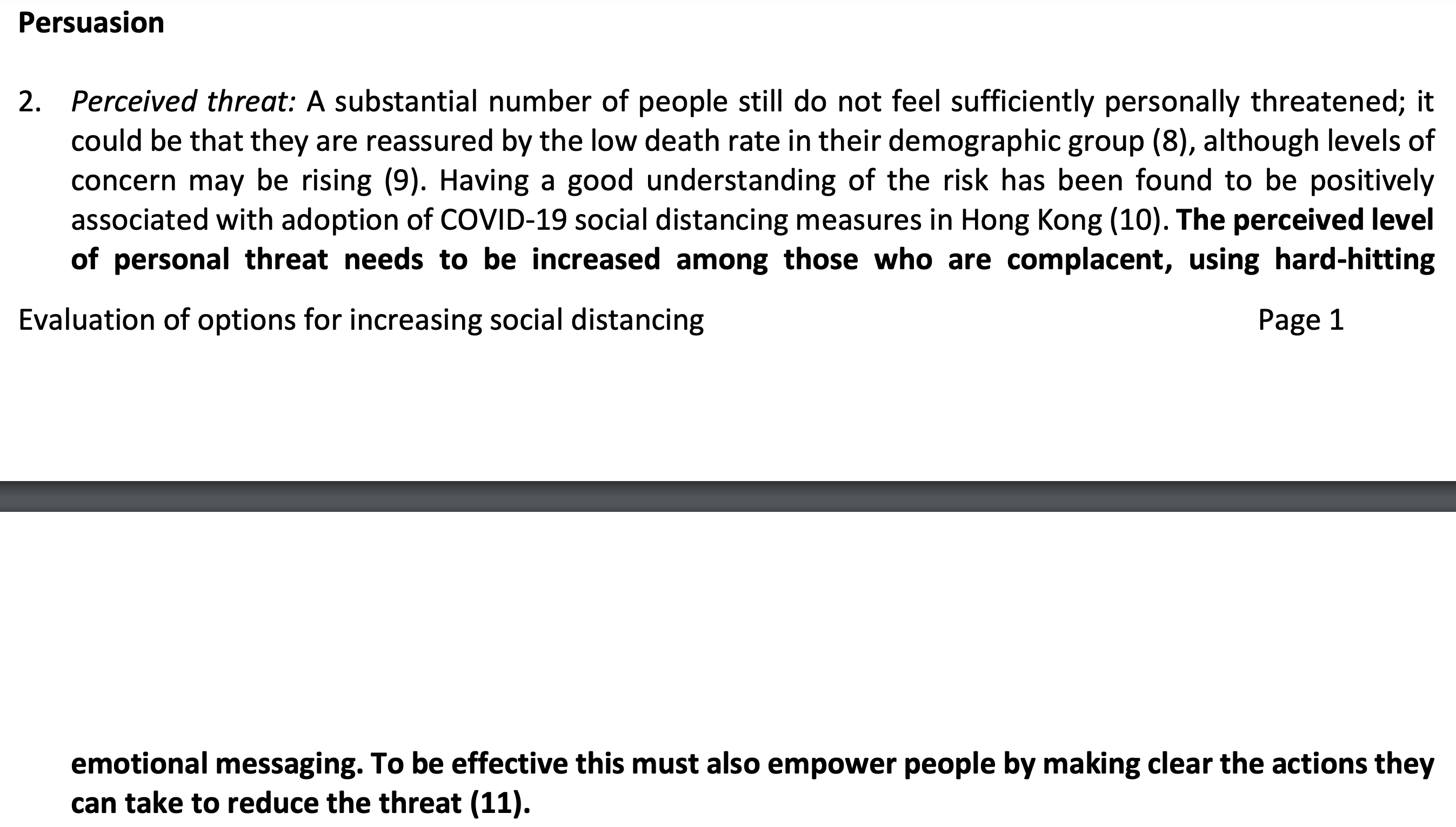

Indeed; the Government does have a role to play in this, the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies on the 22nd March 2020, explicitly urged the Government to increase the sense of personal threat in society - but it is critical to note that panic buying was occurring weeks before such measures were implemented.

British society seems quick to jump to accusing central Government for all ills in their lives, but perhaps the most critical task for Government, and society as a whole, is that of improving cohesion, community and self-responsibility within the UK population.